Wednesday with words

September 22, 2010 — antatraoreHot season in Mali

April 23, 2010 — faithdanceHot season has arrived in Mali,*) no question about that, and this is mentioned on all kinds of platforms, such as Facebook and different blogs.

Here is a collection of funny tidbits from some Facebook friends and their friends:

You know it’s hot season in Mali when…

…you don’t need a towel, you air-dry in less than a minute.

…you refer to a day that doesn’t hit 115F / 46C as a “cool day.”

…you stand in the shower with your clothes on so you can have the illusion of cooling as your clothes dry.

…you take cold showers on purpose.

…even the Malians say, “Boy, it’s hot.”

…you are showering your kids and they scream, “No, it’s too hot. Turn on the cold water.” You reply, “This IS the cold water!”

…you can bend your candles into any fancy shape you want.

…your clothes feel like they’ve been freshly ironed when you put them on.

…your ankles sweat.

…corned beef melts on the table before you get to make sandwiches.

…you can fry eggs on your forearm.

…all the expats in Kayes head for the border.

…the only time you are completely dry is immediately after a shower.from Sharon & friends: You know it’s hot season in Mali when… (Facebook status)

Coping strategies:

Here are some excerpts from Jennifer’s blog about her strategies for hot season (to read all of them go here)

WATERBEDS: When waterbeds became popular in the 70s and 80s, someone decided they were the solution to a missionary’s problems in hot climates. I remember people telling us we HAD to get one. After all, if you can get a good night’s sleep, it goes a long way toward helping one cope with the strains of the day (which is true). …

The problem is that water tries to equalize itself with the air temperature. For a large body of water, like an ocean, the difference remains significant, so you can still have a cool dip in hot weather. But a relatively small body of water, like a mattress, quickly approaches the ambient temperature. Even if the room cools off at night, the warm water is contained in a huge rubber “bottle” which releases heat slowly – a month or more after the end of hot season, but certainly not in a few hours! …

Seemingly, this did not work for her, but it has worked fine for me so far. It certainly contributes to the miracle that I can sleep in a room that has 92-95F /33-35 C. As she explains, you have to cool down the water mattress with soaked towels and fans. Depending on how hot it is, I do this one to three times per day.

SHOWERS: Did you notice how many people in the responses at the beginning referred to showers? Don’t be surprised if you come to my house and I answer the door dripping wet – if it’s not sweat, then I’ve just taken a shower fully clothed. It’s even more effective if I can sit in front of a fan afterwards. …

SLEEPING OUTSIDE: We might have avoided the waterbed fiasco altogether if we had investigated how the local people tolerate the heat. Quite simply, they move outside to sleep at night. It’s even better for those whose houses have a flat, concrete roof to sleep on. …

This was one of the big advantages of living in the village which I miss very much since moving to Bamako. In the village we had a second building with a flat roof where we could sleep on whenever the inside of the house got too hot. The only disadvantage – it is difficult to get down form the roof with all your stuff (mattress, mosquito net, sheets, alarm clock, ..) when you are overtaken by a sand storm. 😉

FANS, SWAMP COOLERS, AND AIR CONDITIONERS: We have lots of fans, but when it gets really hot they just blow hot air. However, they aren’t too bad if your clothes are wet. A swamp cooler is an evaporative cooler or humidifier, common in the American southwest, that blows air through water. …

This is the advantage of living in Bamako where we have 220V instead of just 12V like in the village – I can have an air conditioner and the fans are more powerful. The disadvantage is that the air conditioners are not cheap and use a lot of electricity. For this reason I have one only in my office, but not in the rest of the house. My new home came with a swamp cooler but so far it has only cost me a lot of repairs.

SWIMMING: There’s a great swimming spot on the river about 10 miles out of town and we enjoy going out there, especially when our kids are home. Not far from there is a rocky area with swimming holes and waterfalls which stay quite cool even in hot season, and we love to explore there as well. During Spring Break we sat on a flat rock under a waterfall which was a fabulous experience. …

VACATION: This is the ultimate solution to Beating the Heat: leave town. We save up all our vacation time and head west to the coast of Senegal for the month of May. Interior Senegal is just as hot as Mali, but the coast is quite pleasant (besides the obvious benefit of being close to our children). And in just 15 days from now, that’s what we’ll be doing. …

My personal favorite is the ‘African Air-conditioner’ – similar to Swamp coolers that are based on the principle of evaporative heat loss, the same principle is at work when I cover myself with a wet sheet before going to sleep. Sometimes I have to get up during the night to make the sheet (cloth, pagne) wet again, but in general it helps a lot to cool down the body and sleep well. The same happens when you hang a wet towel around your neck during the day.

Top Ten Reasons to Love Hot Season in Mali:

10. Working late at the office takes on a whole new significance – Free AC.

9. The Malians finally agree with you when you say it is hot.

8. If you have problems deciding what shirt to wear, no problem. You’ll be wearing at least 3 today.

7. A chance to practice your Fahrenheit-Celsius conversion with big numbers like 41 or 46C (106F or 115F).

6. For those of us who have no hot water heaters, we can finally take a hot shower!

5. It’s a great time of the year to do swamp cooler maintenance.

4. Everyday household tasks become an extreme sport.

3. Clothes have that wonderful “fresh out of the dryer” feel when you take them out of the closet.

2. The oven is automatically “pre-heated”, and hey – most food is already pre-cooked.

1. A daily occasion to regale your facebook friends with complaints about how hot it is (just as they are expressing joy that it is finally getting up to 70F!)from Tim: Top 10 reasons to love Hot Season in Mali (Facebook note)

*) The question is maybe whether hot season has ever left. This years ‘cold season’ was everything else than cold, even for Malian standards. Already in February temperatures often felt like hot season.

A belated ‘Wednesday with words’ – Nadi’s story in pictures

February 18, 2010 — antatraore

Nadi and her family in January 2007.

Nadi’s foot three years ago (Jan 2007). At this time we did not know what illness she had since more than 15 years. It had gotten so bad, that she rarely left the house because walking was too painful. Over the last years three doctors who saw the photos confirmed that she had Madura foot. Since then it had gotten worse to the point that the pain kept her from eating. She was only skin and bones when she arrived in Bamako in November 2009.

The French doctors who did the amputation remarked how she improved visibly even just a few days after the surgery.

Nadi at the end of January 2010 – the healing of the wound took longer than predicted but in the end it healed well and was “bien matelasser” (well padded) as a colleague of the orthopedic technician remarked. 😉

At the beginning of February 2010 – the orthopedic technician puts a cast on Nadi’s stump to make a print of it.

Today was her last day of practice at the technician’s office and afterward she went home with two legs. It still needs a lot of practice until the walking with the heavy prosthesis will be smooth but it is wonderful seeing her walk after 20 years of illness.

Traffic patterns

November 12, 2009 — antatraoreIn a class on Folk Religion we read Paul Hiebert’s article on “Traffic Patterns in Seattle and Hyderabad”. His comparison between Seattle and Hyderabad made me smile because after having lived in two African countries and visited several others, I knew exactly what he was talking about.

Hiebert writes about the traffic in Hyderabad:

The first impression many Americans have is that Hyderabad traffic has no order. Obviously, this is false. So many people could not travel with so few accidents if there were none. Why, then, do Americans jump to this conclusion?

I am familiar with this kind of frustration when things don’t work like we think they should. Even if the official traffic rules in Mali are patterned after a Western example (France), there are often cultural rules that come into the mix.

Global Road Warrior has the following information for business people coming to Mali –Mali: Road Conditions

Driving conditions in the capital of Bamako can be particularly difficult and dangerous. Few traffic signals function regularly, and drivers often do not follow the rules of the road. In particular, the small, green, van-like buses called “bashays” pay no heed to oncoming traffic, and bashay drivers are known to change lanes unexpectedly without looking. Please exercise extreme caution when driving in Bamako.

Over the years of living in Mali and navigating the traffic in Bamako, I discovered the following principles:

1) Egalitarianism – everybody gets a chance

When you come to a crossing from a non-priority street, after some time of waiting, you have the right to go, priority or not. This is often indicated by stretching out your palm towards the oncoming traffic on the priority road. When I saw this for the first time, I got really upset. I had priority and this was a violation of the rules. Plus, the person seemed to behave like a policeman but wasn’t one, and I thought: “Who the heck does he think he is?!?!” Once I understood the principle, I could see the advantage as I am, too, sometimes coming from a non-priority street, and if it went according to the rules, I might have to wait “until the cows come home.”

2) Cow path mentality – go wherever there is room

This leads me to the second principle. Most people in Bamako are more influenced by village life, than town life. Most grew up in a village or have spent a longer time with relatives in a village. Also, this kind of village mentality does not easily change and is passed on to second and third generation of town folk. I know from experience that there are few clearly marked roads in a village or between villages, and even less tarmac roads. So when the rain makes a stretch of road unusable, this is not a huge problem. People just find another way to get around the spot. By the end of the rainy season there are many different ways to get from point A to point B. The paths of cow herds moving up and down the country vary even more. Wherever there is no obstacle, you can go, and when there is an obstacle you just find a new path.

How does this now apply to the traffic in Bamako?

It’s simple – you go or drive wherever there is room. If there is a line of cars on the right side of the road, waiting for the traffic light to turn green, and nobody is coming on the left side of the road, you will of course use this “empty space” to circumvent the obstacle. This applies especially to bikes, motorbikes and pus pus (push carts). When you want to go over the Niger river on the new bridge, you will arrive on a kind of cloverleaf intersection / ingress ramp to join a two lane street. During rush hour these two lanes easily turn into four and a half lanes, as cars and motorbikes keep pushing their way in (four with cars, a half one with motorbikes). Amazingly, this does not happen when there is a policeman in sight.

3) Negotiation – establishing relationships at every crossing

The third principle does not only apply to Bamako traffic, but to many other areas of Malian culture. Who gets to go and who has to wait is a matter of negotiation, not of rules. You have to make eye contact and try to discern the other persons intentions, which is often communicated by hand gestures and/or head movements. When I discovered this principle (thanks to a discussion about traffic with Ibrahima), at first I was annoyed. Is it not so much easier and more efficient to follow rules instead of negotiating at every crossing who gets to go? You can go much faster on a priority road, when you know that everybody sticks to the rules and nobody will step or drive into your way who shouldn’t. Plus, it is so much less stressful! This is certainly the normal reaction of a Westerner and rather ethnocentric. Interestingly, Hiebert quotes an experience from 1974 in London that showed that traffic lights and marked lanes do not guarantee more effectiveness.

On the other hand, negotiating your position in relationship to others is very much an overarching principle in many areas of life in Mali. So it is only natural to also apply it to the traffic. In a way it is a more people oriented approach, while rules easily diminish other people to objects.

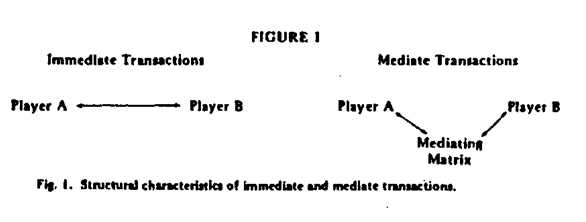

Hiebert calls the two approaches immediate and mediate transactions:

Marked lanes, stop lights, and signs controlling space introduce a particular type of order to traffic, an order based on mediated transactions. In immediate transactions players calculate their moves by observing the actions of the other players. In mediate transactions they calculate their moves not directly on what others are doing, but on their relationship to a third mediating agency (Figure 1).

Hyderabad traffic seems to have a lot of similarity with Bamako traffic. Similar to my remark above, Hiebert also concludes that:

The introduction of mediate transactions tends to standardize and depersonalize interaction. In immediate transactions a player is related directly to other players. …. In mediate transactions a player responds to an impersonal matrix. The result is a measure of standardization and of depersonalization. The difference between the two types of transactions is roughly analogous to that between tennis and golf.

Of course, there are many more aspects that come into play: the fact that the majority of road users is probably illiterate and has not learned in school how to behave in different traffic situations (I am not even sure whether thosse that go to school have had any kind of road safety education or not); people riding a motorbikes do not need a license and therefore had no instruction on traffic rules; most participants have no idea that a truck can’t stop as fast as a pedestrian; women have the tendency to cast their eyes down and not look men into the eyes, which some also do when crossing the road; few have heard that it is wise to also keep the road users behind oneself in mind, e.g. when moving to the middle of the road or avoiding an obstacle; there is a patron-client thinking that makes the richer person more responsible than the penniless road user, which means that even if it is not your fault, the one with money gets to pay the bill; Western traffic rules were made for situations were bikes are a minority – in Bamako cars are several times outnumbered by bikes and this creates whole different dynamic.

All of this makes Bamako traffic a challenge for everybody, but even more so for expatriates.

Ref:

Hiebert, Paul G. “Traffic Patterns in Seattle and Hyderabad.” Journal of Anthropological Research 32, no. No. 4 Winter (1976): 326-36.

Scenery, machinery or people?

October 20, 2009 — antatraoreIn Anthropology we learned about the “scenery, machinery, people” approach of most Westerners: we often divide people in these three groups and treat them accordingly.

– The “scenery people” are for example those that we photograph during our vacations. We see them as decoration or objects on display, not as real people. We do not care whether the photo we are taking respects their dignity or not.

– The “machinery people” are those that we expect to function in a certain way, but again we do not see them as real people. For example, the gas station attendant or the cashier. On a good day, we might see them as people and connect in some personal way, but most of the time we treat them as “machinery” not as people.

– The “real people” are the small group we have a relationship with and care about. We see them as people with individual personalities, emotions, opinions, gifts and needs. On bad days we might expect even people in this group to just function and not require any “maintenance”: such as the burlesque husband coming home from work in the evening who expects his wife to have a meal ready, as well as the newspaper and the slippers, and be left in peace to watch TV by his children because he is tired. In this case he does not see his wife and children as people and does not treat them as such. They are not allowed to have needs.

Whom we expect to just be “scenery” or function as “machinery” is often culturally defined. And this is where culture shock often comes as a natural result.

– The market person in Africa does not function like a cashier in the West, who just rings up the goods we picked and lets us leave without any personal interaction. No matter how small the purchase, you cannot buy anything on an African market without going through a certain amount of greetings, both on arrival and leave taking. Depending on the country you are in and on the type of good you are buying, you will also need to bargain.

○ I remember a story I once heard of a Westerner who did not have the time on one day to do the required bargaining. He told his friend on the market, “Please for once let’s not do it, just ask any price and I will pay it.” His African friend was deeply offended, not – as we might expect – happy about the opportunity to ask for more than usually. For him it was a disregard for his dignity as a human. He had been treated as machinery.

– In many African countries there is a strong awareness of hierarchy but despite of it every employee still expects to be greeted by others in the same organization. Not greeting them robs them of their dignity as humans and reduces them to “machinery.”

○ The context of greetings is one example where I discovered how contradictory courtesy can be. When I come into the office and see two people talking with each other, it feels very impolite to me as European to interrupt the conversation in order to greet them. But this intuition is wrong in the African context. According to African courtesy it would be impolite to not interrupt and walk by them without greeting them. Or as a friend put it – “treat them as if they were trees” – which again expresses the idea of treating others as humans not as things.

– Requesting permission to take the photo of somebody might seem odd for Westerners but is a good rule of thumb in Africa. People do not like being “scenery” but want to be respected as humans. It might mean that you cannot take a picture if a person does not consent to it.

○ Probably there are also different traditional ideas that come into play of what happens to a person’s soul when somebody takes a photo of them. I have rarely heard them stated but only read about these ideas. Even though many things have changed, these ideas might still linger in the back of people’s minds.

○ Another complication is the idea that you might make a lot of money with the photo you are taking. Even if this is not the case for most of us, people have heard about this and want a share in your gain. Some will not give you permission to take a photo without a payment. Since I don’t have enough money to pay everybody whom I photograph, I usually chose not to take that photo. One market lady however managed to convince me nevertheless: “You are happy about the photo, so why don’t you want to give me some happiness, too?”

– Doing everything on your own and alone is unnatural for many people in Africa. Going alone to the market, carrying all your shopping alone, eating alone, staying alone in your room/house, etc. Sharing burdens and joys is an important part of most if not all Africa cultures.

○ Westerners might consider offers to carry their shopping a nuisance. However in African cultures younger people are obliged to honor older people by carrying whatever they have. In return the older person will give a blessing to the younger person. This can be a spoken blessing, in some cases accompanied with spitting (saliva being considered a means of transferring power), or a small coin or other kind of tangible gift. Along the same lines, a market seller feels obliged to send a young person with his customer to help carry the shopping to the car, who then will be expected to give some small token of gratitude to the young helper.

○ The African give and take is not guided by rules of how much to give but by what people have. Many financial requests will be quantified by “whatever you can give.” This puts Westerners in a bind, because we are not used to think in these terms and often have so much more than what we find appropriate to give in such a situation. In addition, local people often have wrong ideas of how much we really have, to the point of seriously believing that our financial supplies are unlimited because we can print our own money.

In all these examples, there are people who want to be seen as people and treated as people which is in contradiction to many of our Western habits and laws of efficiency. The Western habit of just saying “Hi!” and walking by clashes with the African understanding of politeness. Africans would probably never consider a time spend with other people a “waste of time.” My guess is that there is no single situation in African cultures that allows people to treat others “as if they were trees” – trees that you can pass without greeting, that you can expect to function and give you shade or whose photo you can take without permission. People are always people and want to be treated as such, not as “scenery” or “machinery.”

P.S. I know that speaking about “African cultures” or “African” in general is a sweeping generalization that does not do justice to the variety of cultures in Africa. However, I have the impression that the points mentioned above apply to many of them, maybe to all, and possible also to many if not most non-Western cultures.

Bamako (movie)

March 27, 2009 — antatraoreDid you hear about this film that is named after Mali’s capital Bamako and takes place in a court yard of this city? Well, I had heard about it and now I finally managed to see it, thanks to Blockbuster Online. It is a very interesting film. The film’s main languages are French and Bambara, but the DVD includes English subtitles.

The product description on Amazon summarizes it well:

An extraordinary trial is taking place in a residential courtyard in Bamako, the capital city of Mali. African citizens have taken proceedings against such international financial institutions as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whom civil society blames for perpetuating Africa’s debt crisis, at the heart of so many of the continent’s woes. As numerous trial witnesses (schoolteachers, farmers, writers, etc.) air bracing indictments against the global economic machinery that haunts them, life in the courtyard presses forward. Melé, a lounge singer, and her unemployed husband Chaka are on the verge of breaking up; a security guard’s gun goes missing; a young man lies ill; a wedding procession passes through; and women keep everything rolling – dyeing fabric, minding children, spinning cotton, and speaking their minds.

It is the court yard where the filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako grew up. The film basically includes three stories lines woven into each other – the trial, the everyday life in the court yard and the television movie “Death in Timbuktu”. They seem to be completely independent from each other and still are happening in the same place. It makes me think of two transparencies being laid on top of each other.

Sometimes it seems as if they don’t even notice each other: The court carries on, while a teenager passes between judges and audience, carrying a child back and force, women come to the central water faucet and noisily fill their buckets right next to the court audience, the singer demands her little brother to close the back of her dress standing in between two rows of the audience, etc.

Then there are times when they do acknowledge each other: The court pauses when a wedding accompanied by the loud and throaty praise song of a griotte (female praise singer) comes into the court yard; there are megaphones outside the court yard, so other people can listen, but when they want to talk among themselves, they switch off the megaphone; several people seem to listen but then there is no indication in their faces.

Included on the DVD is an interview with Gita Sen (Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era). She beautifully underlines that this coexistence is part of the message of the film: The policies of international institutions and the economic system of the West since the time of the slave trade negatively affect life in Africa. At the same time people carry on with their lives as if nothing has happened, and it is the women who bear the brunt of the load.

It is a movie that needs to be watched several times.

Moskito nets

March 25, 2009 — antatraoreToday in one month is World Malaria Day. It was established in 2007 by the WHO and took place for the first time in 2008. So this is the second time it takes place.

Several organizations have started their announcements and action plans:

to only name a few.

Last year the project “One million faces against malaria” asked Facebook members (who heard about it in time) to exchanged their profile picture with a black square for one day with the goal to “raise awareness of malaria and SHOW THE WORLD WHAT ONE MILLION FACES DYING OF MALARIA EVERY YEAR LOOKS LIKE.”

The video from World Vision shows how mosquito nets could prevent the death of so many children.

Several organizations completely focus on providing more mosquito nets, such as:

- Comic relief and Red Nose Day

- Seattle Sounders FC

- Facebook game African Safari

It is true that there are more than one million children who die each year from malaria (which is already less than when I first arrived in Africa in 1993 when the estimate was two million), the majority are under five years old. This means one child dies every 30 seconds in Africa. Still too many!

So sending mosquito nets to Africa is great, isn’t it? Well, I have mixed feelings about it. One (minor) reason is that I know from experience that the mosquitoes are most active during dusk and dawn, but few children are sleeping during this time. Most children stay up and play until late at night. Nightfall is when the family sits outside in the court yard to eat their evening meal together. Smaller children will fall asleep during this time or shortly after, next to their parents who will sit and talk for a long time into the night. Maybe the parents will use a cloth to wave away flies or mosquitoes but it would be unnatural to separate the small children from the rest of the family, by putting them under the mosquito net inside the house where they would be all alone. Only when the mothers go inside to sleep, they will take their small ones with them. Upper class urban families might have additional smaller mosquito nets, that can be used to protect children sleeping alone. I have seen them on sale in the capital but never anywhere else. It is certainly a good thing to sleep under a mosquito net, and I do it myself, but it is wrong to give the impression that this might prevent children from ever getting bitten by mosquitoes.

And there is another reason:

Ben and Eddie, quoting an article from the Wall Street Journal, raised the issue if sending nets to Africa does not ruin the local businesses that could produce these mosquito nets and therefore perpetuates a cycle of dependency from the West.

I certainly agree, that swamping a region with 100,000 free mosquito nets would have this effect.I am just not convinced that this is what will happen. I have seen the distribution of free mosquito nets in our village. They were usually given as an incentive to pregnant women, encouraging them to come for their pre-natal check-up at the maternity, get their shots and give birth there. I don’t know how these nets had been financed but they certainly did not come in huge quantities drowning out the local production, more like supplementing it. It’s hard to say that this will now suddenly change because of the above mentioned action days, etc.

However, I agree that this principle is at work in many other ways, that “pouring huge sums of money into situations is not a way to achieve goals; not for governments, nor for Christian missions,” (Eddie) because the situation in developing countries is very complex as I have pointed out before. We often do not understand how touching one part of the “mobile” can unbalance the rest of it and will have unintended side effects. This is were sound anthropological research plays an important role. Also, it helps to be in it for the long run and work on our cultural integration, so that we might have true friends that will give us honest answers, instead of telling us what they think we want to hear or what helps them “milk” us better.

The author of the WSJ article, Dambisa Moyo, suggested that cutting off the flow would be far more beneficial. I am not convinced of it.

Eddie summarizes his post by “Stimulating local initiative and ownership takes longer, costs less, is much more effective, but is far harder to do.” And one commenter suggested the use of local supplies and work forces for the production of mosquito nets. I fully agree with both of them.

You know you’ve been in Mali too long when…

March 7, 2009 — antatraoreMost of these have been posted on a Facebook group with this name. I edited some and added my own:

You know you’ve been in Mali too long when…

…you are personally offended by short skirts.

…you reuse Ziploc bags until they literally fall apart and after washing them you stick ’em to the wall to dry.

…you get excited when the thermometer reads only 40°C/104°F.

…you LOVE mangoes (in any forms- bread, dried, juice, whole…).

…you have multiple uses for your Air France eye mask.

…you no longer tremble at Bamako traffic.

…you run outside to see it rain.

…your clothes dry on the line in 10 min.

…you know somebody who has called Jorge Busch or ATT from Armee’s taxi.

…you’ve been offered at least 6 cows and 3 camels as dowry.

…you’ve been asked more than once to become a Malian man’s second or third wife.

…you had Malian women offering their husbands to you because they have pity on you for not being married.

…you find ants in your drink and think… huh, more protein.

…you never stop sweating.

…you have forgotten what real milk tastes like.

…your javel (chlorine) bottle is always at hand.

…you catch yourself saying… Yum- rice and sauce.

…you are cold because it’s only 20°C/68°F and its just too cold.

…you are getting excited when a lizard or gecko is crawling up your room wall because at least the flies and mosquitoes are getting eaten.

…you see a guy carrying a bench or a pile of chairs on his head, or on the back of a moto (moped), and you think nothing of it.

…you received a live chicken as gift from people and knew what to do with it.

…you accept to share a glass of tea the size of a shot with a shop owner.

…you think nothing of a man walking through a gas station selling this tea on a silver platter.

…you don’t notice when the traffic crawls in four lines where there are only two lanes and a bike lane.

…you are not surprised to see two adults and two children riding on one moto.

…you are not shocked when you pass five speed bumps in a row and the sotrama driver doesn’t even slow down.

…you are used to seeing a mud hut next to two large satellite dishes.

…you are content with sitting on one buttock only when riding on a sotrama because the apparentie (driver’s assistant) stuffed more than 20 people in the back of the minivan.

…you are always prepared to stop your car in the middle of nowhere because a herd of cows needs to cross the road.

…you know that it is unwise to offer a lift in you car to women with a calabash on their heads.

…you find it perfectly normal when two finely-dressed women are talking to each and one carries a bag of onions on her head.

…you don’t expect the bus to be air-conditioned because it says so on the outside.

…you know that a non-air-conditioned bus will be cooler than an air-conditioned bus because you can open the windows.

…you hold your paper cash notes from the corner.

…you know that you can’t return from a trip without giving everyone you know a cadeaux (present).

…you get excited when Azar’s got a new stock of cat food.

…you have seen someone with a leg of raw meat from some unfortunate creature strapped to the back of their moto.

…you travel without a toothbrush because you can always find a stick from a nem tree.

…you think of a religious sacrificial object when somebody uses the word “fetish.”

…you shudder away from kissing sounds.

…you realize how boring your dreams are when you run out of mefloquine (malaria prophylaxis).

…your feet are dirty and cracked and stay that way for the first three weeks back in your home country.

…you wonder where all these toubabs (white people) come from when you go home.

…you can’t help saying “toubabou, toubabou, toubabou” when a white person walks by.

…you order Coca light instead of Diet Coke when back home.

…you get back home and realize that you forgot that there is such a thing as a weather forecast.

…you have an instant shock reaction when somebody back home pays or gives something with his/her left hand.

…you have been back home for many years and you still say doni doni (slow slow, little little).

Feel free to suggest more if you know you’ve been in Mali too long because you …